In 2012, together with Iulius Carebia, I spent three weeks at the Korowai, a tribe living in the forests of New Guinea Island. We arrived there without much information and planned to cross their territories finding our way by word of mouth.

After 10 days on boats, starting from Surabaya, in Java, we arrived in Basman, a village at the southern border of the Korowai. From Basman we deepened in the forests and swamps. Our guides were following barely visible tracks, between pounds of dark water hidden by vegetation, water streams and crossing man-made clearings, where we could see houses raised 5-10 meters above the ground. The forest resounded of birds and yodelers. The Korowai constantly make their presence known, “so that they know we are coming and don’t get scared.”

We left Basman escorted by three guys. The Korowai don’t go alone in the forest and never without bows and arrows. The bows are bent ready, and the arrows on hand. They have a fast temper and spontaneous reactions, run or fight.

After three days our guides convinced us that it is not possible to go further. “The waters are too high, we can’t cross them now”. And they just left us at a crossroad, in the middle of the forest, with other guys, and returned to Basman.

We had a few attempts to cross their lands, which we estimated to be a 4-7 days hike, but somehow we never arrived at the destination. The Korowai are winding between the territories of different clans, to avoid the enemies. The conflicts among them are frequent and our guides made no exception. Despite all planning we never walked further than one day, always ending in the house of one of their relatives.

In the forest, our escorts were armed with bows and machetes. Then, besides a kind of suspicion from both sides, they were always expecting to receive something from us, constantly asking for food, tobacco, clothes, tools or money. We didn’t make a team with the guys, an uneasy feeling was keeping a distance between us.

Some Korowai got used to foreigners, coming there in organized trips, 2-3 times a year. 5 mil ID (400 USD) to build a house in a tree, 1 mil for fishing and sago working “show”, 20 mils to organize a sago grub ceremony – aka a tribal party. Everything had a price.

The white men’s guides tout them to stage a “wild tribe” scenario, for their reach customers hunting trophy photos. The porters and camp staff would stay behind the group. “We don’t come dressed when they film”. The others, the “real primitives”, would wait naked for documentary makers and eccentric tourists. One day, we arrived at such a place. No make-up, as we arrived unannounced. We saw a house over 20 meters above the ground, in a treetop, right on the riverside. It looked spectacular. We found out that it has been built for a BBC documentary. The Korowai would build their houses at 5-10 meters from the ground, in the middle of a clearing, where they have gardens.

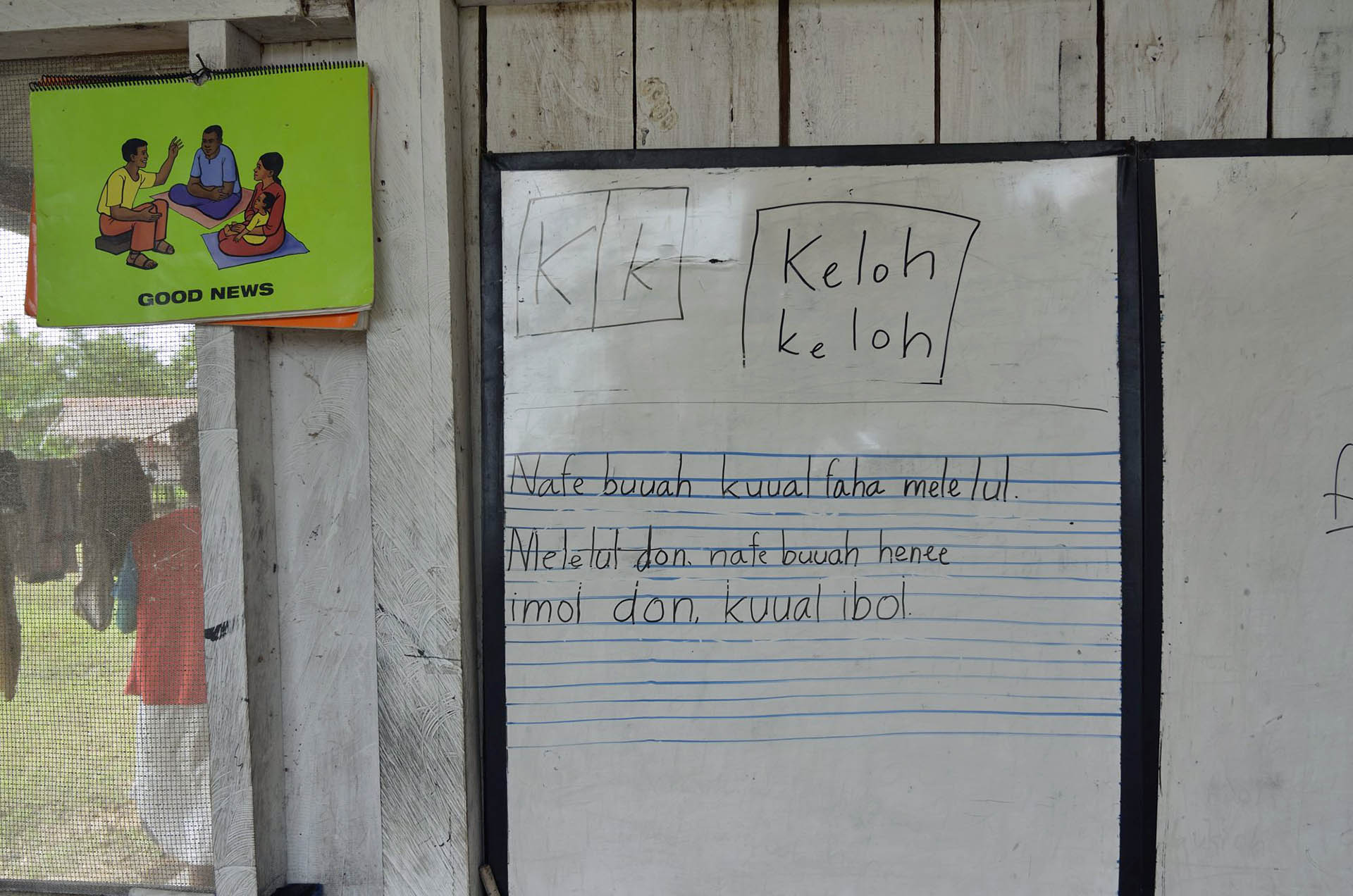

As we are moving in circles, into the Korowas’ forest, we ended up in Yaniruma, a big village between Korowai and Kombai territories, which became our base camp. Yanirumah was established there at the end of the seventies, by Dutch Protestant missionaries. The Korowai don’t build villages, as they go every day into the forest for food, and each family lives on its own territory, hundreds of meters away from others. The few villages found there were settled by missionaries and more recently by Indonesians, in the attempt to take the Korowai out of the forest.

In Yaniruma we stayed at the village clinic, where the paramedics, two great guys from Flores and Sumatra, introduced us to the neighbouring clans.

I spent a night in a tree with a Korowai chief and his stories. When he was not puffing his long pipe or playing a bamboo Jew-harp, he was telling stories with lots of enthusiasm.

Once, he went to town with some friends, and they had nothing to eat, so he came up with a good idea. They stopped a car and robbed the driver. “We ate a lot and kept some money for women (prostitutes) too”. His conclusion: “it’s not good to go to town with women. We, the men, can still find a way, but for women it’s difficult”.

He talked to me proudly of two of his kids. The younger ones went to school, and his older son was in prison, after beating a policeman. “That’s dad’s boy, he broke the door of the cell!” and he smiled, showing his fist to suggest the strength.

He told also me stories about the time when he was a kid and cannibalism was still practised among Korowai. When he was young, he also killed a man. Smiling, he showed me how he shot him with an arrow. “You know, I was naughty when I was young”.

Now, he’s the head of the clan, and he’s in charge to mediate conflicts, women exchanges and murder compensations, swinging between tribal customs, state laws and the young and restless Korowai.

There in his tree-top house, 10 meters above the ground, in the middle of a clearing, I could hear the birds echoing around. And I enjoyed there were no mosquitos at that height. “I build my house up here. I can imitate all the birds”. Following the Korowai rules, the house was separated into two, with two entrances and two stairs-logs. One compartment for him and his wives, the other one for his mother in law. “We cannot meet”, it’s taboo. When one was going out, or coming close to the house, he/she was whistling in a particular way, to mark his/her presence. That night, I felt that I finally arrived at the Korowai. And there was plenty of things to do and stories to hear. But a stamp from my passport ringed the bell. The Indonesian visa was expiring. I left the Korowai with more questions than I had when I arrived.

Back in Yaniruma, we bought a dug-out canoe, to paddle down to a port where we could catch a public boat to a city, where we could take a plane… But we failed, breaking the canoe on the rapids. The GPS, good luck and some jungle experience helped us to return to Yaniruma, cutting straight through the forest. Then, after three days of trekking, we reached Bomakia, a small town where our journey to Korowai ended.