During the weeks I spent with the people from West Sepik villages, I joined them in the swamps, to catch fish.

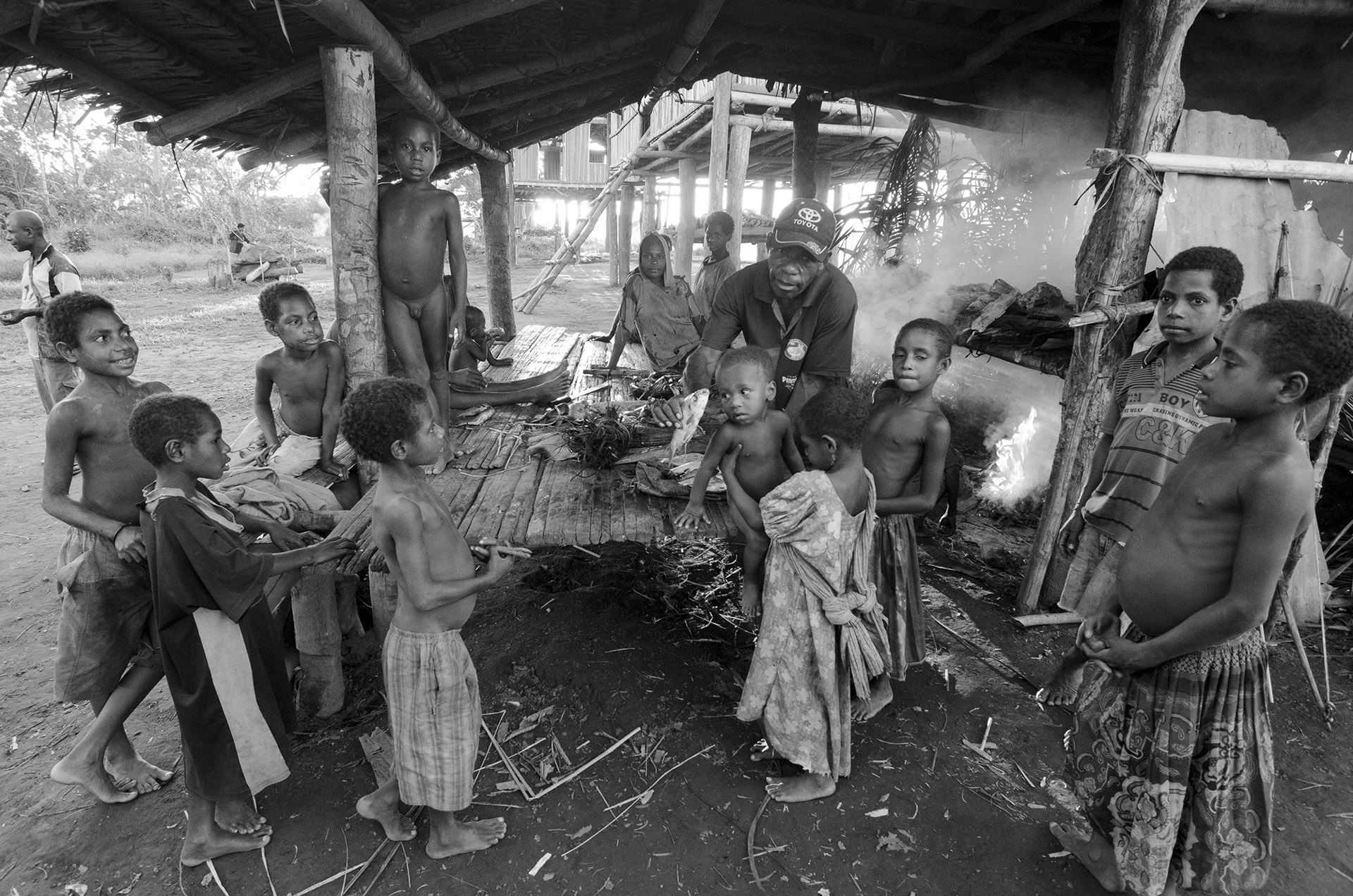

Armed with baskets made of bush-ropes, cane spears, fishing nets, machetes, and smoking logs – for chasing away mosquitoes, drying tobacco and light cigarettes, we hopped on canoes and paddled along the Sepik. When the canoes were pulled aside, we walked into young forest and marshlands, through a maze of one-foot-wide paths, to a pond of murky water hidden in the forest. There, they were smashing poisonous roots, to squeeze them in the water, and then collect the numbed fish. One or two hours was enough for a good catch, which would last a family for a few days.

As there are plenty of flooded forests, the indigenous don’t go often to the same location. Each swamp has its time, depending on rain and the level of Sepik waters. And above everything, some spirits and sorcerers visit the swamps, which must be considered too. One day, a boy died, drowned in a pond nearby the village. “I gat spirit, long kilim em”. Nobody could go back to that water for weeks. And there are also swamps, home of powerful monsters, where people should never go.

Trying to ignore the buzzing mosquitoes and my feet sinking with every step in a muddy soup of vines and thorns, struggling to keep my camera dry, and wiping the sweat from my eyes, distracted me from admiring the landscape. But I remember hearing the living forest surrounding the noisy party. Yodelers, calls, water splashes and laughter were accompanying the moving crowd. With a good mood and plenty of energy, the Sepik people were storming the swamp. When they were gone, the sounds of cicadas and birds settled again around the calm swamp. I noticed this, as I was always behind the group, moving slowly on that terrible terrain.